This is going to be a bit different from the usual format. Instead of looking at a novel on bestvpn.work (part by part), I’m going to have this done in one review. I’m trying to avoid the Dread Curse of Unfinished Postings that seems that have been cast on this here blog.

(Now watch as I decide that the whole review can’t possibly fit into one post, promise a part two and never get around to finishing it)

But, in all seriousness, I would like to thank our humble webmaster for the opportunity to post here. And, while I’m pretty sure I won’t be as funny as Kevin or as insightful as Noel, I will try my best to be good anyway.

Now, on with the review.

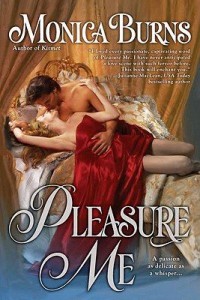

I picked up Monica Burns’ “Pleasure Me” more or less on impulse. the cover caught my eye, but it was the synopsis on the back that really grabbed me. A romance novel set in the late 19th century United Kingdom, featuring a 41-year old courtesan and a younger man…

Anyone who’s followed me on Twitter or read my blog would know of my fondness for older women. I’m also a bit of sucker of romantic movies set before the 20th century. I’ve watched entirely too many films where my thought process something like this:

- Is it romance?

- Does it have corsets?

- What are we waiting for – lets watch!

So when I saw a novel that had an older woman/younger man romance and a period setting, I knew I had to check it out.

As I started reading it, I found myself enjoying it. As the novel opened, our female lead, Lady Ruth Attwood, has just been dumped by her latest patron – for a younger woman, no less. At 41, Ruth doesn’t feel particularly old, but that sort of thing has been happening a lot recently, leaving her to wonder if she should take her savings and retire from the courtesan life.

I liked Ruth right off the bat. The opening chapter presented her strong woman who didn’t fold easily under pressure, someone who could be charming and gracious at one moment and fire off an eloquently cutting zingers in the next. While losing a patron hurt her ego, Ruth was determined not to let the disappointment ruin her life completely. She is as loyal to her servants as they are to her, and, when she loses a patron and with it, a source of income, her first concern is over how that would affect her ability to buy a new building for an orphanage she’s been funding.

Yes – our heroine spends most of her money on orphans. Under other circumstances, that might have been a bit too precious, but, in the context of the novel, it becomes just touching enough to avoid cliche.

While at a society function, Ruth runs into our male protagonist, the 29-year-old Baron Garrick Stratfield. Initially, he came off as a cliche Brooding Love Interest With a Dark Secret. But unlike a lot of characters of this type, he didn’t come off particularly assholish – he came to Ruth’s support when she found herself in the midst of some society drama, and he generally treated people well unless they didn’t deserve it.

As for the brooding thing – well, Garrick was trying to keep people from getting too close. Especially women. For, you see, there was something about him that was so horrible that there was no way any woman could love him.

Then, one chapter later, we find out that his horrible dark secret is the fact that he only had one testicle.

I did a double take. This couldn’t seriously be the horrible secret… could it?

The next few pages made it clear that, yes, it very much could.

At this point, I figured that the novel would either get unintentionally hilarious or somehow make the whole dark secret thing work. Either way, I had to keep reading.

And, in the end, I’m still not entirely sure what to think.

On one hand, it didn’t really get unintentionally hilarious – at least not in the way that’s mockable. During the course of the novel, we learn why Garrick thinks his birth defect is so horrible – it had to do with a traumatic incident in Garrick’s teenage years and generally terrible environment he grew up in. It’s telling that, once Ruth found out the truth, pretty much shrugged it off (and then spent the better part of the next few chapters trying to build up Garrick’s self-confidence). By the last third of the novel, it’s clear that the real issue isn’t Garrick’s “deformity” – it’s his struggle to achieve a sense of self-confidence and self-worth.

At the same time, as the novel progressed, I came across other things that started to bother me. I liked the early courtship between Garrick and Ruth, full of back-and-forth quippery and discussions of the moral implications of literature. And, later, when Garrick starts to trust Ruth enough to (slowly, oh so very slowly) reveal his secrets, and the readers get to see the defensiveness and vulnerability beneath the broodiness. It is interesting to watch his character growth as he realizes that being vulnerable didn’t make him “less of a man.”

But as the novel continued, Ruth seemed to have been losing chunks of her personality – the wit, her wilfullness, her ability to set boundaries and enforce them. Yes, the whole “being around the man I love makes me want to stop arguing and do what he wants” is a trope as old as romance genre, but it was weird seeing a character who rebuked Garrick after he (accidentally) insulted her in the beginning of the book let him pretty much ignore her requests about half a book later.

And then, there is Garrick himself. At the beginning of the novel, he was presented as standoffish, driven and a bit pigheaded. He was a man who worked hard to establish the “I am the Alpha Male, I am strong and I get what I want” persona to compensate for his deep-seated insecurities. He likes being in control because he grew up barely in control of anything and because, when he let his guard down, it tended to come back to haunt him. One would have hoped that, once Garrick gained more genuine self-confidence, he would have learned to relax a little and not worry so much about getting his way. But, if anything, he became more pushy and arrogant. When he offended Ruth earlier in the novel, Garrick seemed genuinely contrite, and he tried to apologize. But when, toward the end of the novel, Garrick tried to convince Ruth to marry him, he borderline bullied her into accepting it.

(I say “borderline” because it also involved an attempt to actually address her reservations and try to ease her concerns, but there were several lines and moments that still made me uncomfortable).

There is also the issue of how the novel handled conflict (such as it was). In romance novels, it is customary for protagonists to face obstacles before they get together. Those obstacles tend to form what passes for conflict in the genre. And there is nothing wrong with that per se (personally, I don’t think stories necessarily need to have any big conflicts at all – I’m perfectly content to read about things just happening so long as they happen in an interesting way). But the problem with the novel is that a lot of those obstacles are kind of… weak. They get built up as something significant, even insurmountable, only to have the author resolve them a chapter or two later with barely a fuss.

Garrick doesn’t want Ruth to see him naked, but he also wants to screw her? Ruth suggests a blindfold. Ruth winds up seeing his nether regions anyway? She, as I mentioned earlier, pretty much shrugs it off. Even when Garrick is threatened with a prison sentence for a crime he didn’t commit, the whole plot winds up resolved so quickly that one has to wonder why the author even bothered.

And finally – this is something of a personal pet peeve. The novel makes a big deal out of Ruth’s age – and proceeds to downplay it as much as possible when actually describing her. Yes, she is in her 40s, the novel says, but she actually looks much younger. Come to think of it, Ruth barely shows any signs of aging at all.

There are many women in their 40s who look pretty damn good without the aid of Botox and what have you, but they don’t look like 20-somethings. Aging process affects us all – some less than others, but it’s still there. The Lucy Liu looks pretty damn good in Elementary, but you’d never mistake her for the Lucy Liu that appeared in Ally McBeal.

Now, I realize that a lot of this has to do with the novel’s primary target audience, who are, most likely, women around Ruth’s age. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to appeal to their hopes and dreams, to assure them that 20-something men would still find them beautiful. But I don’t think the audience is particularly well-served if they present an unrealistic ideal of what a woman their age would look like.

Still, the novel has many things going for it. The writing style is descriptive and engaging, the characterization is well-handled, the parts that are meant to be amusing genuinely are. One can tell that the author spent time researching period detail – and while i don’t know enough about the period to be absolutely sure everything is accurate, I appreciate the effort. I was impressed with the fact that social standing was a big deal and an important driving force in the plot – as one would expect from the time period (and something that many less skilled writers tend to forget). I particularly like how the novel drew attention to the distinction between what everybody knew but didn’t talk about and what was out in the open (a subtle distinction, but a pretty important one in the context of the novel). And it is nice that Ruth actually has a female friend who supports her through thick and thin (and who feels like a living, breathing person with thoughts and opinions of her own) – something that we don’t see nearly enough with female characters in general.

Well, it looks like it’s time to wrap things up. Thank you for indulging me, dear Made of Fail readers. Maybe someday, I will come back and review something that does turn out to be hilariously terrible.

Then again, given this blog’s record when it comes to multi-part features, perhaps I should quit while I’m ahead.